- Home

- Maher, Stephen

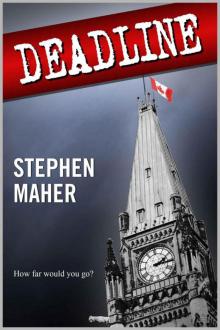

Deadline

Deadline Read online

Deadline

Stephen Maher

Copyright © 2012 Stephen Maher

ISBN 978-0-9918317-0-8

All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental

Cover design: Tim Doyle

Cover photo: Dan Brien

Formatting: Hale Author Services

Contents

Dedication

Psalm 72:6-9

1 – We’ll walk down

2 – PINs and needles

3 – Triangulation

4 – Scoop

5 – Pool report

6 – CRACKIE

7 – Stay where you’re at

8 – Fort Crack

9 – Rats

10 – On thick ice

11 – Good news, bad news

12 – Whoa, la

Acknowledgements

For my parents.

He shall come down like rain upon the mown grass: as showers that water the earth.

In his days shall the righteous flourish; and abundance of peace so long as the moon endureth.

He shall have dominion also from sea to sea, and from the river unto the ends of the earth.

They that dwell in the wilderness shall bow before him; and his enemies shall lick the dust.

—Psalm 72:6-9

1 – We’ll walk down

THERE MUST HAVE been something funny in the birthday cake, Captain Isabelle Galarneau liked to joke, because ever since she turned thirty her hips had been expanding.

On August 14, her thirty-first birthday, when it seemed like everything she owned was suddenly tight around the bottom, and she could imagine herself getting fatter and fatter for the rest of her life, alone and increasingly desperate, she had decided to do something about it. Every weekday morning for the past four months, she had gone jogging, listening to eighties pop on her iPod as she ran.

By December, she had lost eight pounds and was managing a slow, steady run of eight kilometres from her condo in downtown Hull, across the Alexandra Bridge, her bum jiggling with every heavy step, then along the Ottawa River on the Ontario side, below Parliament Hill, to the Chaudière Bridge, where she’d cross back to Quebec and head home to stretch, shower, eat yogurt and dress for work.

Galarneau was a registered nurse in the military, a member of the Disaster Assistance Response Team, the elite group that was ready to set up a mobile hospital anywhere in the world with 24 hours’ notice. She had to be at her desk at National Defence Headquarters every morning at 8:00, so she started her run at 5:00. Today, the sky was still dark as she ran down the slope, through a copse of bare hardwoods, from the Alexandra Bridge to the system of eight locks where the Rideau Canal flows into the Ottawa River. There was a white sheet of fresh snow, and she had to lean back and choose her steps carefully to avoid slipping on the steep trail.

Of the eight locks, only the highest gate was closed this morning, so Galarneau had to jog uphill before she could cross the canal, her thighs aching as she pounded up the concrete steps. She sang along tunelessly to ABBA as she ran. She stopped singing when she put her foot on the walkway and caught sight of the body in the water.

A man floated face-down, his arms by his sides, the jacket of his blue pin-striped suit spread out in the water, right there, about six feet below her, pressed by the current against the lock door.

Galarneau froze and swore in French: “Calice!”

She looked around and saw a thin, grey-bearded fellow in a colourful Lycra outfit approaching the walkway, pushing a bike.

“There’s a guy in the water,” she shouted, and then she took a deep breath and jumped into the freezing canal. The water was only two feet deep as the canal had been drained for the winter, and she landed hard on her heels and tumbled backwards, falling onto her bum and going under.

The cold was terrible. There was already a thin crust of ice forming where the surface of the water met the stone wall of the canal, and ice on the rungs of the old iron ladder set in the stone face.

Galarneau staggered to her feet, shivering and grimacing, grabbed the body by the shoulder and flipped it over. The man was young and lightly built, with sandy hair and a little goatee. His eyes were closed and his lips blue. There was no way she could get him out of the water, so she got onto her knees, pulled him up into her lap, checked his mouth, pinched his nose and started to give him mouth-to-mouth. His mouth was cold and his skin was clammy and blue. She lifted her head to take a deep breath. Above her, the cyclist peered over the edge, a look of concern on his face.

“Hey,” she shouted up to him. “You want to call an ambulance?”

He ran off and she returned to her work.

Karen Stevens arched one blonde eyebrow when the house manager, Phillipe, stepped into the sunroom at the back of 24 Sussex Drive.

Most mornings, she shared breakfast with her husband, Bruce Stevens, the prime minister, and their two teenage daughters, but this morning was different. For one thing, the girls were at a friend’s house for a sleepover. For another, breakfast was a few minutes late. And Phillipe wasn’t carrying the usual bowl of fruit salad, but two huge plates loaded with peameal bacon, sausage, home fries, fried eggs, baked beans and slabs of buttery toast. There was even a little pot of cretons – a pork spread made with lard.

Stevens, who had been up working for hours already, put down his briefing book and gave his wife a tiny smile as she looked in confusion from him to Phillipe to the breakfasts.

“Phillipe, did Chef decide we deserve a little treat today?” he asked.

“That’s right, Prime Minister,” said Phillipe, smiling as he laid down the plates. “It was Chef’s idea.”

Stevens watched a smile spread across his wife’s face – a smile that creased the fine lines around her eyes. It had been a long time since he’d seen her smile like that.

“Did you hear that, honey?” he said, cutting into the peameal bacon. “Chef thinks we deserve a treat.”

She beamed back at him. “So you’ve decided then? And today’s the day.”

He grinned at her, his mouth full, and raised his eyebrows.

Before he could answer, she was up and around the table and pulling him into her arms.

As he held her, he was surprised to feel tears running down her cheeks.

Detective Sergeant Devon Flanagan had to wait outside the ICU while the doctor looked at the floater. He wasn’t at all happy about it. He had two centre-ice tickets to see the Leafs play the Senators, and after some challenging negotiations with his ex-wife, he had arranged to take his eight-year-old son, Jason. He had been sure that he’d get to the game on time, since he was on early shift this week. Then he and his partner caught the floater. Now he had the sinking feeling that he wouldn’t be able to make the game. The thought of calling his son to cancel ate at his stomach, which was already feeling sour, thanks to too much coffee.

He sat for a minute, scratched his grey head, fiddled with his cell phone, put it away, took a sip of cold coffee, pulled his phone out again, and decided to call his partner.

“Hey, how’s it going?”

“The same,” said Detective Sergeant Mallorie Ashton. “I got some uniforms walking both sides of the canal. Pretty much finished up here at the locks. We’ve got Ms. Galarneau’s statement, and one from the guy who called it in. Haven’t really found anything that looks like evidence. I think I’m going to shut this down and head into the office, trace Sawatski’s movements last night.

“I’ve been kind of waiting to hear from you, find out if the kid’s going to make it.”

/> “I still have no idea if we’re looking at an accidental drowning or what,” said Flanagan. “I’m still waiting for the doctor. Hopefully she’ll be done soon.”

“Did you call the family?” asked Ashton.

“Yeah,” said Flanagan. “That wasn’t much fun. They’re likely in the air now, flying in from St. John’s.”

The door opened and Doctor Shalini Singh walked in.

“Oh, here’s the doctor,” said Flanagan. “Talk to you soon.”

He stood up and reached to take the doctor’s hand. She was about 35, tall and slim.

“Sorry to keep you waiting, detective,” she said. “I wanted to make sure Mr. Sawatski was stable before I left him.”

“I understand,” said Flanagan, flipping open his notebook. “Tell me, how is he? Is he going to make it?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “He’s breathing on his own now, and his heart is pumping. I can’t see any reason why he won’t survive, but I can’t make any promises. There are often complications in near drownings, and patients have been known to die several days after seeming to recover. I don’t think that’s likely in this case, though, because most deaths like that are caused by damage to the lungs caused by inhaling water. And this man didn’t have water in his lungs. That’s why he’s alive.”

“Does that mean he wasn’t in the water for long?” asked Flanagan.

“No. In about 10 per cent of drowning deaths, the victim’s airway is sealed off, which prevents water from entering the lungs. It’s known as dry drowning. That seems to have happened in this case, and it likely saved this man’s life. It markedly increases the chance of someone being successfully resuscitated.” Dr. Singh paused. “Mr. Sawatski was lucky. His airway closed off. He was found by someone who knew that she should keep giving him mouth-to-mouth even though he appeared to be dead. And the water was very cold, which probably kept him alive.”

Flanagan looked up from his notebook.

“So how long was he in the water?”

“It’s impossible to know for sure. When someone’s face is immersed in cold water, it triggers the mammalian diving reflex, which slows the body’s metabolism. If the water is cold – and we’re talking about the Rideau Canal in December – then the effect is more pronounced. The body cuts off blood flow to the extremities and focuses on keeping blood in the heart and the brain. There have been cases of children being revived after hours in very cold water. With a young man, it wouldn’t be that long. Probably thirty minutes at the most.”

The doctor leaned back and waited for the next question.

“So what’s the prognosis?” asked Flanagan.

“Well, complete recovery is unlikely,” said the doctor. “He has almost certainly suffered brain damage as a result of oxygen deprivation. The brain has ways of repairing itself, but we won’t know the extent of the damage for days. Right now, he’s alive and recovering, against the odds. He’s a lucky man.”

Flanagan looked up at her.

“I don’t know whether I’d call him lucky or not to have survived,” he said.

The doctor gave him a thin smile. “Where there’s life, there’s hope,” she said.

“Is there any way you can tell how he ended up in the canal?” he asked. “We have no way of knowing just yet whether this is an accident or whether somebody tried to kill this young fellow.”

“Well, that’s really your job,” she said. “I don’t know how he ended up in the water, whether he could swim, if he was conscious when he entered the water, any of that stuff. People do drown all the time. I’ve sent away blood tests so we’ll find out whether he had alcohol or drugs in his system.”

Flanagan had run out of questions. He put his notebook away. “Can I have a look at him?”

She led him to the private room where Ed Sawatski lay underneath a white sheet and blanket. He was connected to a respirator, a heart monitor and an IV drip.

“I thought you said he was breathing on his own,” said Flanagan.

“Yes,” said the doctor, “he is, but we don’t want to take any chances so we’ll leave him on the respirator for now.”

Flanagan stared down at the thin, handsome, blank face. By looking through his wallet on the banks of the canal, he had learned that Sawatski was a 28-year-old staffer on Parliament Hill, but he didn’t know much more. The young man had close-cropped sandy hair and a little goatee. He was very pale. Flanagan peered at him but the face told him nothing. He took out his digital camera and took several pictures.

“Can I pull back the blankets for a moment, doctor?” he asked.

Dr. Singh walked over and felt her patient’s head with the back of her hand.

“Okay,” she said, “but please be quick. His temperature is still low.”

Flanagan pulled the blankets down carefully. Sawatski was wearing a hospital gown.

Flanagan took a picture, then lowered the camera.

“Tell me, doctor,” he said, pointing at Sawatski’s wrists, where there was a dull blue discoloration. “Did you notice those marks when you examined him?”

“No,” she said. “What is it?”

“I believe those are handcuff bruises,” he said. “Looks like we might have an attempted murder on our hands.”

Jack Macdonald awoke with a start and sat up straight in bed when he heard the first trill of his cell phone. He opened his eyes and in a flash felt the hangover: sandpaper mouth, throbbing head, cramped lungs. He blinked his sore, dry eyes to clear his fuzzy vision, and looked around in confusion at his room, strewn with dirty clothes. He squinted. The clock said 9:30 a.m. The phone rang again.

“Lord Jesus,” he croaked.

He looked down and noted with surprise that he had slept in his suit, on top of the blankets, on his back.

When the phone rang a third time, he turned his head and discovered he had a kink in his neck.

The BlackBerry was in the side pocket of his jacket. He grabbed it and cleared his throat but his voice still sounded hoarse and froggy: “Hello. Jack Macdonald.”

“Hello,” said a woman’s voice. “I’m calling for Ed Sawatski.”

“Well, you’ve got Jack Macdonald here,” he said.

The woman was silent for a moment.

“That’s odd,” she said. “He left me a message yesterday, said it was important that I call him at this number, and only at this number.”

Jack wanted desperately to end the conversation. His neck hurt, and he urgently needed to pee.

“I’m sorry, but he must have left you the wrong number,” he said. “We’re friends. Maybe he got mixed up, told you my number by mistake. Why don’t you leave me your name and number and I’ll get him to call you back.”

The woman paused before she spoke. “Mr. Sawatski’s message said that he works in the office of the justice minister, and that it was important that I call,” she said. “Do you work with him there? I’m trying to figure out why someone from the justice minister’s office would call me.”

Macdonald got out of bed and shuffled toward the bathroom. “No, ma’am,” he said. “I’m a reporter for the Evening Telegram. I have no idea why he would call you. He and I were out together last night. Perhaps he had my phone number on his mind. I’m sure he’ll get in touch, though, once I let him know.”

Macdonald stood in the bathroom, aching to get off the phone.

“Oh, you’re a Newfoundlander,” she said. “So am I. Is Mr. Sawatski also? It doesn’t sound like a Newfoundland name.”

“Yes,” he said. “He is a Newfoundlander. We went to Memorial University together. Want me to get him to call you?”

She paused again. “Very well. Tell him, please, that Ida Gushue returned his call. I’ll be out for a time this morning but I’ll be in this afternoon.”

“I’ll let him know right away. Thanks,” he said, and hung up before the conversation could drag on any longer.

He peed for a long time, drank some water from his cupped hands and swallowed three Ty

lenol. He barely recognized the face in the mirror, with its matted dark hair, deep bags under bloodshot eyes, its pale, blotchy, stubbly skin. He wanted nothing more than to get back in bed, but he was already a half-hour late for work and had to get moving.

He walked carefully to the kitchen, rinsed a dirty cup and filled it with yesterday’s cold coffee. He choked some of it down, fumbled in his suit jacket for his cigarettes, and lit one. The smoke hurt his lungs, but he needed the nicotine. He leaned on the sill of the grimy window and looked out at the snow falling on the parking lot. He drank coffee, smoked and tentatively moved his neck, trying to work out the kink. The cheap window rattled as the wind blew the snow against it, and he could feel the cold coming in.

After his coffee and cigarette, he went back to his bedroom, where he spent a few unpleasant minutes trying to find clean clothes, before concluding that the rumpled suit he was wearing was the cleanest thing he had, despite the wine stain on the left lapel. Back in the bathroom he undressed, hung the jacket on a hanger next to the shower so the steam would take out some of the wrinkles, and stood there for a long time, letting the hot water work on his neck. After he’d towelled off and dressed in his bedroom, moving carefully to protect his neck, he picked up the BlackBerry from the bedside table to call Sawatski. He punched in his password, but it didn’t work. He gaped at the screen:

Ed Sawatski

Property of:

Department of Justice, Office of the Minister

613 555-0139

Macdonald grabbed the holster on his belt and pulled out his own phone. In his foggy state, he hadn’t noticed that he was in possession of two BlackBerrys. He sat down on the edge of his bed and tried to work out why he had a cell phone in each hand.

Stevens paused when they reached the last of the agenda items for the day. He looked down at his notes, and then around at the twenty-eight faces at the long oak table – twenty-seven cabinet ministers and his chief of staff. They were seated around the huge, wooden table in the cabinet room of the Centre Block on Parliament Hill, one floor above the foyer of the House of Commons.

“There’s one piece of new business,” he said as he looked around the table. “This morning I told Karen that I’ve decided not to lead the party into the next election.”

Deadline

Deadline